71.Clearly assign responsibilities.

Eliminate any confusion about expectations and ensure that people view the failure to achieve their goals and do their tasks as personal failures. The most important person is the one who is given the overall responsibility for accomplishing the mission and has both the vision to see what should be done and the discipline to make sure it’s accomplished by the people who do the tasks.

72.Hold people accountable and appreciate them holding you accountable.

It’s better for them, for you, and for the community. Slacker standards don’t do anyone any good. People can resent being held accountable, however, and you don’t want to have to tell them what to do all the time. Instead, reason with them, so that they understand the value and importance of being held accountable. Hold them accountable on a daily basis. Constant examination of problems builds a sample size that helps point the way to a resolution and is a good way to detect problems early on before they become critical. Avoiding these daily conflicts produces huge costs in the end.

- 72A. Distinguish between failures where someone broke their “contract” from ones where there was no contract to begin with. If you didn’t make the expectation clear, you generally can’t hold people accountable for it being fulfilled (with the exception of common sense—which isn’t all that common). If you find that a responsibility fell through the cracks because there was no contract, think about whether you need to edit the design of your machine.

73.Avoid the “sucked down” phenomenon.

This occurs when a manager is pulled down to do the tasks of a subordinate without acknowledging the problem. The sucked down phenomenon bears some resemblance to job slip, since it involves the manager’s responsibilities slipping into areas that should be left to others. Both situations represent the reality of a job diverging from the ideal of that job. However, the sucked down phenomenon is typically the manager’s response to subordinates’ inabilities to do certain tasks or the manager’s failure to properly redesign how the responsibilities should be handled in light of changed circumstances. You can tell this problem exists when the manager focuses more on getting tasks done than on operating his machine.

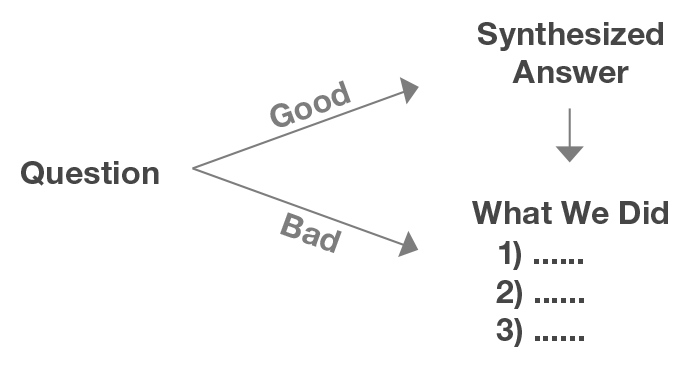

- 73A. Watch out for people who confuse goals and tasks, because you can’t trust people with responsibilities if they don’t understand the goals. One way to test this: if you ask a high-level question (e.g.,) “How is goal XYZ going?”) a good answer will provide a synthesis upfront (e.g., of how XYZ is, in fact, going overall), and then support that assessment with the tasks done to achieve the goal. People who see the tasks and lose sight of the goals will just explain the tasks that were done and not make the connection to how those tasks relate to the machine that produces outcomes and achieves goals.

74.Think like an owner, and expect the people you work with to do the same.

You must act in the interest of our community and recognize that your well-being is directly connected to the well-being of Bridgewater. For example, spend money like it’s your own.

75.Force yourself and the people who work for you to do difficult things.

It’s usually easy to make things go well if you’re willing to do difficult things. We must act as trainers in gyms act in order to keep each other fit. That’s what’s required to produce the excellence that benefits everyone. It is a law of nature that you must do difficult things to gain strength and power. As with working out, after a while you make the connection between doing difficult things and the benefits you get from doing them, and you come to look forward to doing these difficult things.

- 75A. Hold yourself and others accountable. It is unacceptable for you to say you won’t fight for quality and truth because it makes you or other people uncomfortable. Character is the ability to get yourself to do the difficult but right things. Get over the discomfort, and force yourself to hold people accountable. The choice is between doing that properly or letting our community down by behaving in a way that isn’t good for you or the people you are “probing” and coaching.

76.Don’t worry if your people like you; worry about whether you are helping your people and Bridgewater to be great.

One of the most essential and difficult things you have to do is make sure the people who work for you do their jobs excellently. That requires constantly challenging them and doing things they don’t like you to do, such as probing them. Even your best people, whom you regularly praise and reward, must be challenged and probed. You shouldn’t be a manager if you have problems confronting people or if you put being liked above ensuring your people succeed.

77.Know what you want and stick to it if you believe it’s right, even if others want to take you in another direction.

78.Communicate the plan clearly.

People should know the plans and designs within their departments. When you decide to divert from an agreed-upon path, be sure to communicate your thoughts to the relevant parties and get their views so that you are all clear about taking the new path.

78A. Have agreed-upon goals and tasks that everyone knows (from the people in the departments to the people outside the departments who oversee them). This is important to ensure clarity on what the goals are, what the plan is, and who is responsible to do what in order to achieve the goals. It allows people to buy into the plan or to express their lack of confidence and suggest changes. It also makes clear who is keeping up his end of the bargain and who is falling short. These stated goals, tasks, and assigned responsibilities should be shown at department meetings at least once a quarter, perhaps as often as once a month.

78B. Watch out for the unfocused and unproductive “we should…(do something).” Remember that to really accomplish things we need believable responsible parties who should determine, in an open-minded way, what should be done; so it is important to identify who these people are by their names rather than with a vague “we,” and to recognize that it is their responsibility to determine what should be done. So it is silly for a group of people who are not responsible to say things like “we should…” to each other. On the other hand, it can be desirable to speak to the responsible party about what should be done.

79.Constantly get in synch with your people.

Being out of synch leads to confused and inefficient decision-making. It can also lead you in conflicting directions either because 1) you are not clear with each other, which often generates wildly differing assumptions, or 2) you have unresolved differences in your views of how things should proceed and why. Getting in synch by discussing who will do what and why is essential for mutual progress. It doesn’t necessarily entail reaching a consensus. Often there will be irreconcilable differences about what should be done, but a decision still needs to be made, which is fine. The process of getting in synch will make it clear what is to be done and why, even if it cannot eliminate difference. One of the most difficult and most important things you must do, and have others do, is bring forth disagreement and work through it together to achieve a resolution. Recognize that this process takes time. It can happen any way people prefer: discussion, e-mail, etc. You must have a workable process for making decisions even when disagreements remain. I discuss such a process in the earlier section on getting in synch.

80.Get a “threshold level of understanding”

—i.e., a rich enough understanding of the people, processes, and problems around you to make well-informed decisions.