141.To perceive problems, compare how the movie is unfolding relative to your script

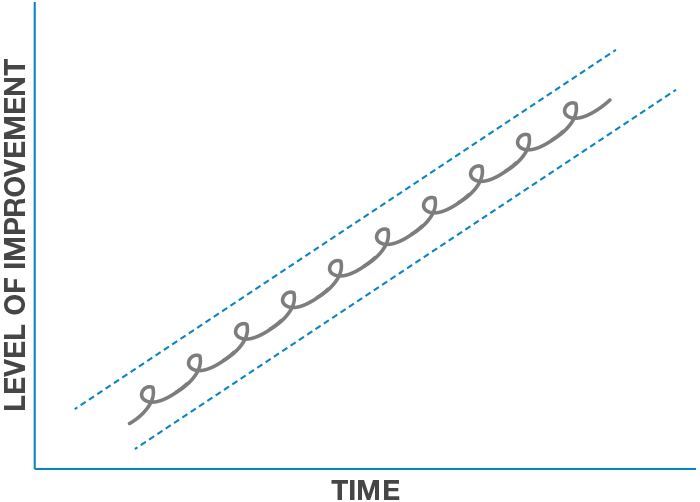

—i.e., compare the actual operating of the machine and the outcomes it is producing to your visualization of how it should operate and the outcomes you expected. As long as you have the visualization of your expectations in mind to compare with the actual results, you will note the deviations so you can deal with them. For example, if you expect improvement to be within a specific range…

… and it ends up looking like this…

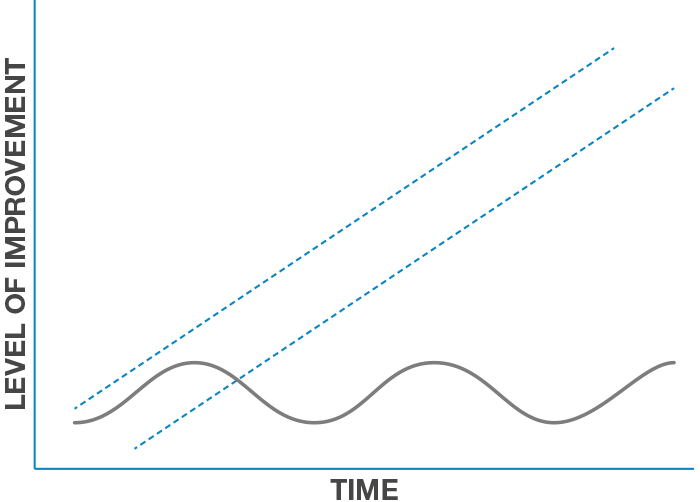

… and it ends up looking like this…

… you will know you need to get at the root cause to deal with it. If you don’t, the trajectory will probably continue.

142.Don’t use the anonymous “we” and “they,” because that masks personal responsibility—use specific names.

For example, don’t say “we” or “they” handled it badly. Also avoid: “We should...” or “We are...” Who is “we”? Exactly who should, who made a mistake, or who did a great job? Use specific names. Don’t undermine personal accountability with vagueness. When naming names, it’s also good to remind people of related principles like “mistakes are good if they result in learning.”

143.Be very specific about problems; don’t start with generalizations.

For example, don’t say, “Client advisors aren’t communicating well with the analysts.” Be specific: name which client advisors aren’t doing this well and in which ways. Start with the specifics and then observe patterns.

144.Tool: Use the following tools to catch problems: issues logs, metrics, surveys, checklists, outside consultants, and internal auditors.

Issues log: A problem or “issue” that should be logged is easy to identify: anything that went wrong. The issues log acts like a water filter that catches garbage. By examining the garbage and determining where it came from, you can determine how to eliminate it at the source. You diagnose root causes for the issues log the same way as for a drilldown (explained below) in that the log must include a frank assessment of individual contributions to the problems alongside their strengths and weaknesses. As you come up with the changes that will reduce or eliminate the garbage, the water will become cleaner. In addition to using issues logs to catch problems, you can use them to measure the numbers and types of problems, and they can therefore be effective metrics of performance. A common challenge to getting people to use issues logs is that they are sometimes viewed as vehicles for blaming people. You have to encourage use by making clear how necessary they are, rewarding active usage, and punishing non-use. If, for example, something goes wrong and it’s not in the issues log, the relevant people should be in big trouble. But if something goes wrong and it’s there (and, ideally, properly diagnosed), the relevant people will probably be rewarded or praised. But there must be personal accountability.

Metrics: Detailed metrics measure individual, group, and system performance. Make sure these metrics aren’t being “gamed” so that they cease to convey a real picture. If your metrics are good enough, you can gain such a complete and accurate view of what your people are doing and how well they are doing it that you can nearly manage via the metrics. However, don’t even think of taking the use of metrics that far! Instead, use the metrics to ask questions and explore. Remember that any single metric can mislead. You need enough evidence to establish patterns. Metrics and 360 reviews reveal patterns that make it easier to achieve agreement on employees’ strengths and weaknesses. Of course, the people providing the information for metrics must deliver accurate assessments. There are various ways to facilitate this accuracy. A reluctance to be critical can be detected by looking at the average grade each grader gives; those giving much higher average grades might be the easy graders. Similarly helpful are “forced rankings,” in which people must rank coworker performance from best to worst. Forced rankings are essentially the same thing as “grading on a curve.” Metrics that allow for independent grading across departments and/or groups are especially valuable.

Surveys (of workers and of customers).

145.The most common reason problems aren’t perceived is what I call the “frog in the boiling water” problem.

Supposedly, if you throw a frog in a pot of boiling water it will immediately jump out. But if you put a frog in room-temperature water and gradually bring the water to a boil, the frog will stay in place and boil to death. There is a strong tendency to get used to and accept very bad things that would be shocking if seen with fresh eyes.

146.In some cases, people accept unacceptable problems because they are perceived as being too difficult to fix. Yet fixing unacceptable problems is actually a lot easier than not fixing them, because not fixing them will make you miserable.

They will lead to chronic unacceptable results, stress, more work, and possibly get you fired. So remember one of the first principles of management: you either have to fix problems or escalate them (if need be, over and over again) if you can't fix them. There is no other, or easier, alternative.

146A. Problems that have good, planned solutions are completely different from those that don’t. The spectrum of badness versus goodness with problems looks like this--

a) They’re unidentified (worst)

b) Identified but without a planned solution (better)

c) Identified with a good, planned solution (good)

d) Solved (best)

However, the worst situation for morale is the second case: identified but without a planned solution. So it’s really important to identify which of these categories the problem belongs to.

147.DIAGNOSE TO UNDERSTAND WHAT THE PROBLEMS ARE SYMPTOMATIC OF

148.Recognize that all problems are just manifestations of their root causes, so diagnose to understand what the problems are symptomatic of.

Don’t deal with your problems as one-offs. They are outcomes produced by your machine, which consists of design and people. If the design is excellent and the people are excellent, the outcomes will be excellent (though not perfect). So when you have problems, your diagnosis should look at the design and the people to determine what failed you and why.

149.Understand that diagnosis is foundational both to progress and quality relationships.

An honest and collaborative exploration of problems with the people around you will give you a better understanding of why these problems occur so that they can be fixed. You will also get to know each other better, be yourself, and see whether the people around you are reasonable and/or enforce their reasonableness. Further, you will help your people grow and vice versa. So, this process is not only what good management is; it is also the basis for personal and organizational evolution, and the way to establish deep and meaningful relationships. Because it starts and ends with how you approach mistakes, I hope that I have conveyed why I believe this attitude about and approach to dealing with mistakes is so important.

150.Ask the following questions when diagnosing.

These questions are intended to look at the problem (i.e., the outcome that was inconsistent with the goal) as a manifestation of your “machine.” It does this first by examining how the responsible parties imagined that the machine would have worked, then examining how it did work, and then examining the inconsistencies. If you get adept at the process, it should take 10 to 20 minutes. As previously mentioned, it should be done constantly so that you have a large sample size and no one case is a big deal.

1) Ask the person who experienced the problem: What suboptimality did you experience?

2) Ask the manager of the area: Is there a clear responsible party for the machine as a whole who can describe the machine to you and answer your questions about how the machine performed compared with expectations? Who owns this responsibility?

Do not mask personal responsibility—use specific names.

3) Ask the responsible party: What is the “mental map” of how it was supposed to work?

A “mental map” is essentially the visualization of what should have happened.

To be practical, “mental maps” (i.e., the designs that you would have expected would have worked well) should account for the fact that people are imperfect. They should lead to success anyway.

4) Ask the owner of the responsibility: What, if anything, broke in this situation? Were there problems with the design (i.e., who is supposed to do what) or with how the people in the design behaved?

Compare the mental map of “what should have happened” to “what did happen” in order to identify the gap.

If the machine steps were followed, ask, “Is the machine designed well?” If not, what’s wrong with the machine?

5) Ask the people involved why they handled the issue the way they did. What are the proximate causes of the problem (e.g., “Did not do XYZ”)? They will be described using verbs—for example, “Harry did XYZ.” What are the root causes? They will be descriptions. For example: inadequate training/experience, lack of vision, lack of ability, lack of judgment, etc. In other words, root cause is not an action or a reaction—it is a reason.

Be willing to touch the nerve.

6) Ask the people involved: Is this broadly consistent with prior patterns (yes/no/unsure)? What is the systematic solution? How should the people/machines/responsibilities evolve as a result of this issue?

Confirm that the short-term resolution of the issue has been addressed.

Determine the steps to be taken for long-term solutions and who is responsible for those steps. Specifically:

Are there responsibilities that need either assigning or greater clarification?

Are there machine designs that need to be reworked?

Are there people whose fit for their roles needs to be evaluated?