101.Make accurate assessments.

Since truth is the foundation of excellence and people are your most important resource, make the most precise personnel evaluations possible. This accuracy takes time and considerable back-and-forth. Your assessment of how responsible parties are performing should be based not on whether they’re doing it your way but on whether they’re doing it in a good way. Speak frankly, listen with an open mind, consider the views of other believable and honest people, and try to get in synch about what’s going on with the person and why. Remember not to be overconfident in your assessments as it’s possible you are wrong.

101A. Use evaluation tools such as performance surveys, metrics, and formal reviews to document all aspects of a person’s performance. These will help clarify assessments and communication surrounding them.

101B. Maintain “baseball cards” and/or “believability matrixes” for your people. Imagine if you had baseball cards that showed all the performance stats for your people: batting averages, home runs, errors, ERAs, win/loss records. You could see what they did well and poorly and call on the right people to play the right positions in a very transparent way. These would also simplify discussions about compensation, incentives, moving players up to first string, or cutting them from the team. You can and should keep such records of your people. Create your baseball cards to achieve your goals of conveying what the person is like. I use ratings, forced rankings, metrics, results, and credentials. Baseball cards can be passed to potential new managers as they consider candidates for assignments.

102.Evaluate employees with the same rigor as you evaluate job candidates.

Ask yourself: “Would I hire this person knowing what I now know about them?” I find it odd and silly that interviewers often freely and confidently criticize job candidates despite not knowing them well, yet they won’t criticize employees for similar weaknesses even though they have more evidence. That is because some people view criticism as harmful and feel less protective of an outsider than they do of a fellow employee. If you believe accuracy is best for everyone, then you should see why this is a mistake and why frank evaluations must be ongoing.

103.Know what makes your people tick, because people are your most important resource.

Develop a full profile of each person’s values, abilities, and skills. These qualities are the real drivers of behavior, and knowing them in detail will tell you which jobs a person can and cannot do well, which ones they should avoid, and how the person should be trained. I have often seen people struggling in a job and their manager trying for months to find the right response because the manager overlooked the person’s “package.” These profiles should change as the people change.

104.Recognize that while most people prefer compliments over criticisms, there is nothing more valuable than accurate criticisms.

While it is important to be clear about what people are doing well, there should not be a reluctance to profile people in a way that describes their weaknesses. It is vital that you be accurate.

105.Make this discovery process open, evolutionary, and iterative.

Articulate your theory of a person’s values, abilities, and skills upfront and share this with him; listen to his and others’ response to your description; organize a plan for training and testing; and reassess your theory based on the performance you observe. Do this on an ongoing basis. After several months of discussions and real-world tests, you and he should have a pretty good idea of what he is like. Over time, this exercise will crystallize suitable roles and appropriate training, or it will reveal that it’s time for the person to leave Bridgewater.

106.Provide constant, clear, and honest feedback, and encourage discussion of this feedback.

Don’t hesitate to be both critical and complimentary—and be sure to be open-minded. Training and assessing will be better if you frequently explain your observations. Providing this feedback constantly is the most effective way to train.

106A. Put your compliments and criticisms into perspective. I find that many people tend to blow evaluations out of proportion, so it helps to clarify that the weakness or mistake under discussion is not indicative of your total evaluation. Example: One day I told one of the new research people what a good job I thought he was doing and how strong his thinking was. It was a very positive initial evaluation. A few days later I heard him chatting away for hours about stuff that wasn’t related to work, so I spoke to him about the cost to his and our development if he regularly wasted time. Afterward I learned he took away from that encounter the idea that I thought he was doing a horrible job and that he was on the brink of being fired. But my comment about his need for focus had nothing to do with my overall evaluation of him. If I had explained myself when we sat down that second time, he could have better put my comments in perspective.

106B. Remember that convincing people of their strengths is generally much easier than convincing them of their weaknesses. People don’t like to face their weaknesses. At Bridgewater, because we always seek excellence, more time is spent discussing weaknesses. Similarly, problems require more time than things that are going well. Problems must be figured out and worked on, while things that are running smoothly require less attention. So we spend a lot of time focusing on people’s weaknesses and problems. This is great because we focus on improving, not celebrating how great we are, which is, in fact, how we get to be great. For people who don’t understand this fact, the environment can be difficult. It’s therefore important to 1) clarify and draw attention to people’s strengths and what’s being done well; and 2) constantly remind them of the healthy motive behind this process of exploring weaknesses. Aim for complete accuracy in your assessments. Don’t feel you have to find an equal number of “good and bad” qualities in a person. Just describe the person or the circumstances as accurately as possible, celebrating what is good and noting what is bad.

106C. Encourage objective reflection —lots and lots of it.

106D. Employee reviews: While feedback should be constant, reviews are periodic. The purpose of a review is to review the employee's performance and to state what the person is like as it pertains to their doing their job.

A job review should have few surprises in it—this is because throughout the year, if you can’t make sense of how the person is doing their job or if you think it’s being done badly, you should probe them to seek understanding of root causes of their performance. Because it is very difficult for people to identify their own weaknesses, they need the appropriate probing (not nitpicking) of specific cases by others to get at the truth of what they are like and how they are fitting into their jobs.

From examining these specific cases and getting in synch about them, agreed-upon patterns will emerge. As successes and failures will occur in everyone (every batter strikes out a lot), in reviewing someone the goal is see the patterns and to understand the whole picture rather than to assume that one or a few failures or successes is representative of the person. You have to understand the person’s modus operandi and that to be successful, they can’t be successful in all ways—e.g., to be meticulous they might not be able to be fast (and vice versa). Steve Jobs has been criticized as being autocratic and impersonal, but his modus operandi might require him being that way, so the real choice in assessing his fit for his job is to have him the way he is or not at all: that assessment must be made in the review, not just a theoretical assessment that he should do what he is doing and be less autocratic.

In some cases, it won’t take long to see what a person is like—e.g., it doesn’t take long to hear if a person can sing. In other cases, it takes a significant number of samples and time to reflect on them. Over time and with a large sample size, you should be able to see what people are like, and their track records (i.e., the level and the steepness up or down in the trajectories that they are responsible for, rather than the wiggles in these) will paint a very clear picture of what you can expect from them.

If there are performance problems, it is either because of design problems (e.g., the person has too many responsibilities) or fit/abilities problems. If the problems are due to the person’s inabilities, these inabilities are either because of the person’s innate weaknesses in doing that job (e.g., if you are 5-foot-2, you probably shouldn’t be a center on the basketball team) or because of inadequate training to do the job. A good review, and getting in synch throughout the year, should get at these things.

The goal of a review is to be clear about what the person can and can’t be trusted to do based on what the person is like. From there, “what to do about it” (i.e., how these qualities fit into the job requirement) can be determined.

107.Understand that you and the people you manage will go through a process of personal evolution.

Personal evolution occurs first by identifying your strengths and weaknesses, and then by changing your weaknesses (e.g., through training) or changing jobs to play to strengths and preferences. This process, while generally difficult for both managers and their subordinates, has made people happier and Bridgewater more successful. Remember that most people are happiest when they are improving and doing things that help them advance most rapidly, so learning your people’s weaknesses is just as valuable for them and for you as learning their strengths.

108.Recognize that your evolution at Bridgewater should be relatively rapid and a natural consequence of discovering your strengths and weaknesses; as a result, your career path is not planned at the outset.

Your career path isn’t planned because the evolutionary process is about discovering your likes and dislikes as well as your strengths and weaknesses. The best career path for anyone is based on this information. In other words, each person’s career direction will evolve differently based on what we all learn. This process occurs by putting people into jobs that they are likely to succeed at, but that they have to stretch themselves to do well. They should be given enough freedom to learn and think for themselves while being coached so they can be taught and prevented from making unacceptable mistakes. During this process they should receive constant feedback. They should reflect on whether their problems can be resolved by additional learning or stem from innate qualities that can’t be changed. Typically it takes six to 12 months to get to know a person in a by-and-large sort of way and about 18 months to change behavior (depending on the job and the person). During this time, there should be periodic mini-reviews and several major ones. Following each of these assessments, new assignments should be made to continue to train and test them. They should be tailored to what was learned about the person’s likes and dislikes and strengths and weaknesses. This is an iterative process in which these cumulative experiences of training, testing, and adjusting direct the person to ever more suitable roles and responsibilities. It benefits the individual by providing better self-understanding and greater familiarity with various jobs at Bridgewater. This is typically both a challenging and rewarding process. When it results in a parting of ways, it’s usually because people find they cannot be excellent and happy in any job at Bridgewater or they refuse to go through this process.

109.Remember that the only purpose of looking at what people did is to learn what they are like.

Knowing what they are like will tell you how you can expect them to handle their responsibilities in the future. Intent matters, and the same actions can stem from different causes.

109A. Look at patterns of behaviors and don’t read too much into any one event. Since there is no such thing as perfection, even excellent managers, companies, and decisions will have problems. It’s easy, though often not worth much, to identify and dwell on tiny mistakes. In fact, this can be a problem if you get bogged down pinpointing and analyzing an infinite number of imperfections. At the same time, minor mistakes can sometimes be manifestations of serious root causes that could cause major mistakes down the road, so they can be quite valuable to diagnose. When assessing mistakes it is important to 1) ask whether these mistakes are manifestations of something serious or unimportant and 2) reflect on the frequency of them. An excellent decision-maker and a bad decision-maker will both make mistakes. The difference is what causes them to make mistakes and the frequency of their mistakes.

There is also a difference between “I believe you made a bad decision” and “I believe you are a bad decision-maker,” which can be ascertained only by seeing the pattern. Any one event has many different possible explanations, whereas a pattern of behavior can tell you a lot about root causes. There are many qualities that make up a person. To understand each requires 1) a reliable sample size and 2) getting in synch (i.e., asking the person why and giving feedback). Some qualities don’t require a large sample size—e.g., it takes only one data point to know if a person can sing—and others take multiple observations (five to 10). The number of observations needed to detect a pattern largely depends on how well you get in synch after each observation. A quality discussion of how and why a person behaved a certain way should help you quickly understand the larger picture.

109B. Don’t believe that being good or bad at some things means that the person is good or bad at everything. Realize that all people have strengths and weaknesses.

110.If someone is doing their job poorly, consider whether this is due to inadequate learning (i.e., training/experience) or inadequate ability.

A weakness due to a lack of experience or training or due to inadequate time can be fixed. A lack of inherent ability cannot. Failing to distinguish between these causes is a common mistake among managers, because managers are often reluctant to appear unkind or judgmental by saying someone lacks ability. They also know people assessed this way tend to push back hard against accepting a permanent weakness. Managers need to get beyond this reluctance.

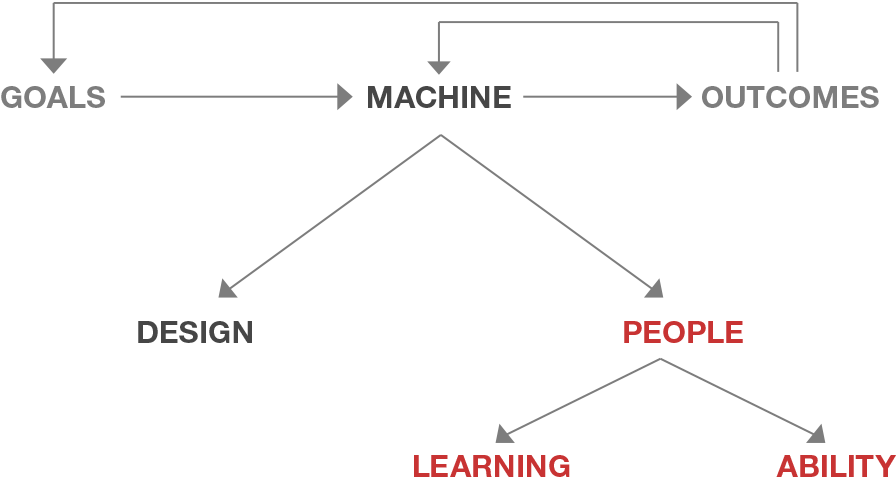

In our diagram of thinking through the machine that will produce outcomes, think about…